Sacred Waters & Spiritual Design: From Maldivian Overwater Mosques to Sri Lankan Lagoon Dagobas

Introduction: The Confluence of Faith and Luxury

Tourism in the Indian Ocean has always been more than beaches, cocktails, and sunsets. For centuries, this oceanic corridor has been a theatre of cultural encounters, spiritual diffusion, and sacred architecture—whether coral-stone mosques in the Maldives, dagobas shimmering across Sri Lanka’s lakes, or shrines tucked into Zanzibar’s coastlines. Today, luxury tourism has begun rediscovering this heritage, borrowing spiritual forms and weaving them into high-end aquatic resorts.

As someone who has spent decades working across these regions—managing resorts, designing guest experiences, and researching cultural tourism—I have witnessed an evolution. Guests no longer travel simply to “stay” in a resort; they seek meaning, atmosphere, and a sense of belonging to something timeless. The rise of spiritual placemaking—embedding sacred design motifs within luxury resorts—reflects this deeper craving.

But this is not a simple task. Sacred architecture carries weight. To reimagine it in the tourism economy requires sensitivity, legal safeguards, and genuine respect for culture. In this article, I explore how overwater mosques in the Maldives and potential lagoon dagoba concepts in Sri Lanka can inspire a new model of tourism—one that balances luxury, faith, and identity.

The Tourism Economy: Setting the Stage with Numbers

Tourism remains the lifeblood of both the Maldives and Sri Lanka.

- In the Maldives, tourism accounts for nearly 30% of GDP and more than 60% of foreign exchange earnings (World Bank, 2023). Visitor numbers crossed 1.7 million in 2019, before COVID-19 temporarily disrupted arrivals. Recovery has been swift, with over 1.8 million visitors recorded in 2023, largely driven by luxury resort stays.

- In Sri Lanka, despite political and economic turbulence, the industry remains resilient. According to the Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA), the island welcomed 1,010,249 tourists in the first half of 2024, a 61.6% increase compared to the same period in 2023. The Central Bank estimates that tourism receipts could surpass USD 4 billion by 2025 if recovery holds steady.

These figures underline why both nations are experimenting with niche differentiation—seeking ways to stand out beyond the “sun, sea, and sand” model. Sacred architecture within resorts is one such frontier.

Sacred Architecture as Spiritual Placemaking

Spiritual placemaking is the act of creating environments that nurture contemplation, respect, and connection—whether or not guests share the same faith tradition. It is less about proselytising and more about aesthetic serenity.

The Maldives provides compelling case studies: overwater mosques constructed with cultural authenticity but also with modern design flourishes. These structures do not only serve local worshippers; they anchor the identity of a place. Imagine praying as turquoise waters ripple beneath a timber floor, or meditating in silence while the horizon dissolves into infinity.

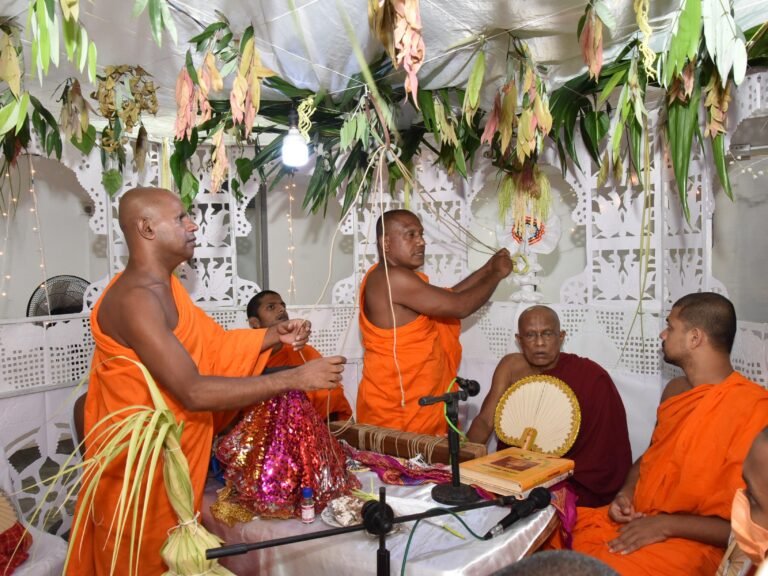

Sri Lanka, too, has its opportunities. The island’s lagoon-side settings—from Negombo to Batticaloa—are ideal for translating dagoba forms into modern aquatic sanctuaries. Such spaces could blend Buddhist architectural silhouettes with meditation platforms, yoga pavilions, or community shrines—without trivialising sacred meaning.

Case Studies: Lessons from Across the Region

1. King Salman Mosque, Malé, Maldives (2022)

Completed with Saudi funding, this grand mosque accommodates 10,000 worshippers and features five minarets symbolising the Five Pillars of Islam. While not part of a resort, it demonstrates how large-scale religious architecture now coexists alongside a booming tourism industry. For designers of aquatic resorts, the lesson is clear: faith is not an afterthought; it is part of urban and national identity.

2. Coral-Stone Mosques of Maldives (UNESCO Tentative List)

Historic coral-stone mosques—such as Hukuru Miskiy in Malé—are masterclasses in adapting fragile marine resources into durable sacred forms. Carved coral blocks interlock with timber beams, creating spaces that are cool, reflective, and timeless. UNESCO has already recognised them as heritage worth preserving. For modern resort architects, these mosques offer inspiration: eco-materials, craftsmanship, and integration with local climate.

3. Soneva Jani Eco-Resort, Noonu Atoll

Soneva Jani redefines overwater luxury. With 25 lagoon villas, retractable roofs for stargazing, and driftwood-inspired architecture, it borrows from natural spirituality without overtly religious motifs. Its design philosophy could be translated into Sri Lankan contexts—for instance, lagoon dagobas that embrace openness and cosmic alignment, not rigid concrete blocks.

4. St. Regis Vommuli & Four Seasons Voavah

Two examples of high-design retreats. St. Regis Vommuli draws from manta ray forms and Maldivian oceanic symbols. Four Seasons Voavah offers a private island experience with exclusivity akin to a sanctuary. Both illustrate how luxury design increasingly leans on symbolism, silence, and immersion—hallmarks of spiritual architecture.

5. Anantara Kihavah’s SEA Underwater Restaurant

Dining six metres below the surface, surrounded by marine life, is a spiritual experience in its own right. Though not a mosque or dagoba, the underwater dining room evokes awe—a core principle of sacred design. Awe transforms luxury from mere indulgence into reverence.

6. Guesthouse Tourism: Local Islands Model

By 2020, over 19% of bed capacity in the Maldives came from 638 guesthouses. Unlike gated luxury resorts, guesthouses on inhabited islands often retain mosques as community centres. Tourists experience not only sun and sand but the rhythm of prayer calls, festivals, and cultural immersion. The key lesson: authentic faith life can co-exist with tourism if framed respectfully.

7. Four Seasons Landaa Giraavaru: Conservation Meets Spiritual Ethics

This resort integrates marine conservation—rehabilitating manta rays, coral nurseries, and turtle sanctuaries. Its ethos echoes Buddhist values of compassion and Islamic stewardship (khalifa). By aligning luxury with ethical guardianship, it becomes a living shrine to nature. Sri Lanka’s lagoon-dagoba resorts could follow this model, marrying heritage with ecological spirituality.

Implications for Sri Lanka: Designing Lagoon Dagobas

Sri Lanka’s tourism planners often look to Maldives for inspiration. But we must avoid imitation and instead leverage our own sacred architecture. The dagoba (stupa) is not merely a religious monument; it is a cosmic diagram representing enlightenment. Imagine:

- Lagoon meditation domes, shaped as miniature dagobas, floating serenely in water.

- Pilgrim-style boardwalks, leading guests from shore to aquatic shrines.

- Inclusive sanctuaries, open to Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and secular seekers.

- Community partnerships, where local monks, artisans, and villagers co-design resort shrines to prevent commodification.

Tourism research shows that 72% of high-spending travelers now seek “transformational experiences” (Booking.com Travel Report, 2023). A lagoon dagoba resort in Sri Lanka could place the island on the map as a leader in transformative, spiritually grounded luxury tourism.

Legal and Ethical Considerations

Sri Lanka must tread carefully. Sacred design cannot become a marketing gimmick. Legal and ethical guardrails include:

- Intellectual Property Act No. 52 of 1979: ensures artisans’ design rights are protected.

- ICCPR Act No. 56 of 2007: mandates non-discrimination and dignity for all religious communities.

- Environmental laws: lagoon shrines must not damage mangroves, coral, or fisheries.

- Clerical consultation: involve monks, imams, priests, and local councils in design approvals.

By adhering to these frameworks, Sri Lanka can create a model of respectful sacred tourism.

Conclusion: From Shores to Spirits

The Maldives has already shown how sacred architecture can inform resort design—from overwater mosques to manta-shaped villas. Sri Lanka now stands at its own threshold. Our lagoons are not just waterscapes; they are canvases for spiritual architecture. If designed with care, lagoon dagobas could position Sri Lanka as a global leader in cultural-spiritual luxury tourism—where faith is not exploited but honoured, and where guests depart not only with photographs but with renewed spirit.

Disclaimer

This article has been authored and published in good faith by Dr. Dharshana Weerakoon, DBA (USA), based on publicly available data from cited national and international sources (e.g., Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, international tourism monitors, conservation bodies), decades of professional experience across multiple continents, and ongoing industry insight. It is intended solely for educational, journalistic, and public awareness purposes to stimulate discussion on sustainable tourism models. The author accepts no responsibility for any misinterpretation, adaptation, or misuse of the content. Views expressed are entirely personal and analytical, and do not constitute legal, financial, or investment advice. This article and the proposed model are designed to comply fully with Sri Lankan law, including the Intellectual Property Act No. 52 of 1979 (regarding artisan rights and design ownership), the ICCPR Act No. 56 of 2007 (ensuring non-discrimination and dignity), and relevant data privacy and ethical standards.

✍ Authored independently and organically through lived professional expertise—not AI-generated.

Further Reading: https://www.linkedin.com/newsletters/outside-of-education-7046073343568977920/

Additional Reading: https://gray-magpie-132137.hostingersite.com/maritime-service-hub/