The Silent Carbon Sink: Monetizing Sri Lanka’s Home Garden (අවුරුද්ද) Biodiversity for Corporate Carbon Offsetting and Community Wellness

How Sri Lanka’s ancestral home gardens can anchor climate finance, rural prosperity, and regenerative tourism

Introduction: A Carbon Asset Hidden in Plain Sight

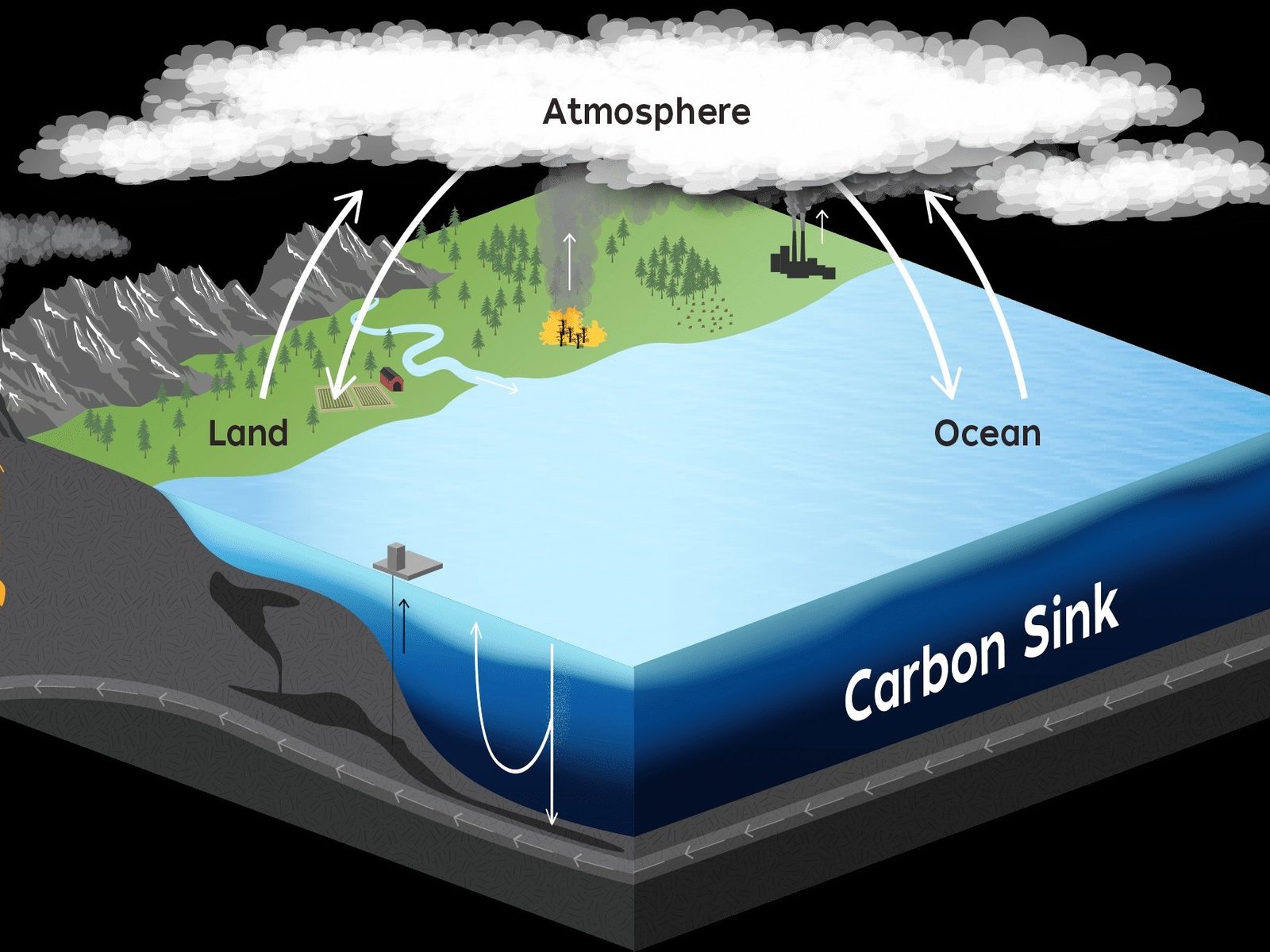

Across Sri Lanka, from the wet-zone villages of Kandy and Galle to the dry-zone settlements of Anuradhapura and Monaragala, millions of families maintain a living system that has quietly endured for centuries: the home garden (අවුරුද්ද). These layered agro-ecological landscapes—often dismissed as subsistence plots—represent one of the most under-recognized carbon sinks, biodiversity reservoirs, and wellness ecosystems in South Asia.

In an era where corporations spend billions of dollars annually on carbon offsets—often in distant continents—Sri Lanka already possesses a nationally distributed, culturally embedded, and community-owned solution. The missing link is not nature. It is valuation, verification, and vision.

This article proposes a policy-safe, ethically grounded, and tourism-aligned framework to monetize Sri Lanka’s home garden biodiversity for corporate carbon offsetting, while simultaneously strengthening community wellness, food security, and experiential tourism.

Sri Lanka’s Home Gardens: A National Ecological Infrastructure

Scale and Distribution

Sri Lanka has an estimated 4.1 million home gardens, covering approximately 15–20% of the country’s total land area. In the wet zone alone, home gardens account for nearly 35% of tree cover outside forests. These gardens typically range from 0.1 to 1 hectare, but their ecological productivity far exceeds their size.

Biodiversity Density

A single Sri Lankan home garden can contain:

- 30–70 plant species

- 15–25 tree species

- Medicinal plants (ayurvedic and traditional)

- Fruit trees, timber species, spices, and vegetables

Studies conducted over decades consistently show that species richness per hectare in home gardens often rivals that of managed forest plantations.

Carbon Sequestration Potential

Conservative estimates indicate that Sri Lankan home gardens store between:

- 50–150 tonnes of carbon per hectare (above and below ground)

- Annual sequestration rates of 2–5 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent per hectare, depending on structure and species composition

At a national scale, this equates to a carbon sink exceeding 30–40 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent, much of it unaccounted for in formal climate reporting.

Why Corporate Carbon Markets Are Looking for Nature-Based Solutions

The Global Carbon Offset Market

- Global voluntary carbon markets exceeded USD 2 billion annually

- Over 65% of corporate buyers now prefer nature-based solutions (NBS) over industrial offsets

- Tourism, aviation, banking, apparel, and technology sectors dominate demand

Corporations increasingly seek offsets that:

- Are community-inclusive

- Deliver co-benefits (biodiversity, livelihoods, wellness)

- Align with ESG reporting and SDGs

Sri Lanka’s home gardens meet all three criteria—authentically and at scale.

From Backyard to Balance Sheet: A Monetization Framework

Step 1: Community Carbon Clusters

Rather than individual plots, village-level carbon clusters (50–200 home gardens) can be aggregated for verification. This reduces transaction costs and ensures equity.

Step 2: Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV)

- Use stratified biomass sampling

- Digital land mapping (non-invasive)

- Annual biodiversity and tree growth audits

This can be managed through local universities, trained youth, and agrarian extension officers.

Step 3: Carbon Credit Issuance (Voluntary Market)

Credits are issued under voluntary standards, focusing on:

- Avoided deforestation

- Enhanced tree cover

- Soil carbon improvement

Step 4: Revenue Distribution Model

A recommended model:

- 60% to household owners

- 20% to community development and wellness programs

- 10% to monitoring and verification

- 10% to national conservation and administration

This ensures transparency and long-term sustainability.

Wellness, Culture, and Tourism: The Triple Dividend

Home Gardens as Living Wellness Spaces

Sri Lankan home gardens are not just productive landscapes—they are therapeutic environments:

- Natural shade and microclimate cooling

- Access to medicinal plants

- Reduced stress and improved nutrition

Global wellness tourism is valued at USD 900+ billion, with travelers increasingly seeking authentic, regenerative experiences.

Experiential Tourism Opportunities

Home garden-based tourism can include:

- Ayurvedic food and herbal walks

- Carbon-neutral village stays

- Indigenous cooking experiences

- Mindfulness and forest-bathing programs

This positions Sri Lanka as a carbon-positive wellness destination, not merely a leisure market.

Case Studies: Lessons from Sri Lanka and Beyond

Case Study 1: Kandyan Forest Gardens (Sri Lanka)

Recognized globally as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS), Kandyan home gardens demonstrate how multi-layered planting sustains livelihoods while conserving biodiversity. Household incomes increased by 20–35% through spice and fruit diversification.

Case Study 2: Kerala Home Garden Carbon Pilots (India)

Smallholder home gardens were aggregated for voluntary carbon markets, generating USD 8–12 per household per year, while improving tree cover and soil health.

Case Study 3: Costa Rica’s PES Model

Costa Rica’s Payment for Ecosystem Services program pays farmers for forest conservation, contributing to over 50% national forest cover recovery and strong eco-tourism branding.

Case Study 4: Bhutan’s Carbon-Negative Identity

Bhutan’s community forestry model integrates culture, carbon neutrality, and tourism, reinforcing its global positioning as a high-value, low-impact destination.

Case Study 5: Indonesia’s Village Carbon Cooperatives

Village-level carbon cooperatives enabled communities to collectively negotiate with corporate buyers, ensuring fair pricing and social safeguards.

Case Study 6: Sri Lankan Organic Village Tourism Initiatives

Pilot organic villages linked to tourism supply chains reported higher farmer incomes, improved nutrition, and enhanced visitor satisfaction.

Case Study 7: Japanese Satoyama Landscapes

Traditional rural landscapes were revitalized through biodiversity credits and eco-tourism, reversing rural depopulation trends.

Economic Impact: What This Means for Sri Lanka

If just 25% of Sri Lanka’s home gardens are enrolled:

- Carbon credits: 8–10 million tonnes CO₂ annually

- Potential revenue: USD 80–150 million per year (at conservative prices)

- Direct beneficiaries: 1 million rural households

This complements tourism earnings without additional land conversion.

Legal, Ethical, and Cultural Safeguards

This model is designed to:

- Respect private land ownership

- Protect indigenous knowledge

- Ensure gender equity in benefit-sharing

- Avoid land grabbing or forced participation

Participation is voluntary, informed, and revocable.

Policy Alignment and National Branding

The home garden carbon model aligns with:

- Sri Lanka’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 1, 8, 13, 15)

- Tourism repositioning toward quality, wellness, and regeneration

It also strengthens Sri Lanka’s global narrative as a nature-positive island economy.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Value from Our Roots

Sri Lanka does not need to invent sustainability. It needs to recognize, value, and modernize what already exists. The home garden—our ancestral system of coexistence—can become a cornerstone of climate finance, community wellness, and next-generation tourism.

By monetizing biodiversity without commodifying culture, Sri Lanka can lead—not follow—the global transition toward regenerative economies.

The silent carbon sink is ready to speak. We must now listen.

Disclaimer

This article has been authored and published in good faith by Dr. Dharshana Weerakoon, DBA (USA), based on publicly available data from national and international sources, decades of professional experience across multiple continents, and ongoing industry insight. It is intended solely for educational, journalistic, and public awareness purposes to stimulate discussion on sustainable tourism models. The author accepts no responsibility for any misinterpretation, adaptation, or misuse of the content. Views expressed are entirely personal and analytical, and do not constitute legal, financial, or investment advice. This article and the proposed model are designed to comply fully with Sri Lankan law, including the Intellectual Property Act No. 52 of 1979, the ICCPR Act No. 56 of 2007, and relevant data privacy and ethical standards. Authored independently and organically through lived professional expertise.

Further Reading: https://www.linkedin.com/newsletters/7046073343568977920/

Further Reading: https://dharshanaweerakoon.com/the-biophilic-bank/